What's wrong with our idea of budgets? Part 2

Any difference between our health budget, and say, our education budget?

In part 1, the answer to the question was, productivity. We showed that 5 percent, or 10 percent, or even, 100 percent, of nothing, is still nothing.

Now, in part 2 of What’s wrong with our idea of budgets?, we are going to show that our health budgets have never been about health.

What do we typically budget for?

WHAT on earth, specifically, are our health budgets for? We say they are for health, but, what is health, to a budgeter? Now if you’ve ever seen any budget in Nigeria, whether federal or state, you will know that for the past 60 years, every budget devotes 70% or more, to salaries and recurrent expenditure.

If our health budget follows that pattern, then health is going nowhere.

Health cannot be achieved by paying health workers. Now don’t get me wrong - these people have worked for their money. But paying salaries is not a health matter at all: it is properly a labor matter, period. It is also an economic matter.

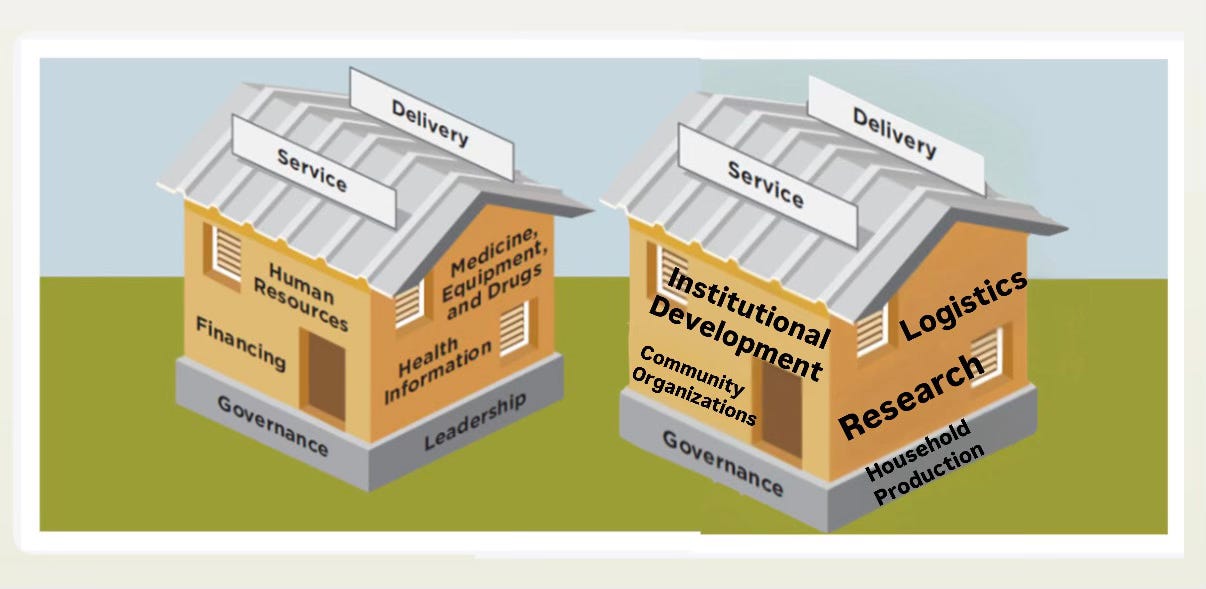

Our health budgets must change their major line items from mostly salaries, to actual health issues: such as capital expenditure, institutional development, research, manufacturing, logistics & service delivery.

These are the ‘moving parts’ of our health systems. For now, who pays for these actual health system parts? Donors. And, even then, only in part. Meaning, these building blocks of health systems are mostly underfunded or unfunded. Can you see now why we have weak to no health systems? It’s not ‘corruption’: it’s that we are misbudgeting and mismanaging the basic idea of money and budgets. Maybe, we’ve never had to think about it?

Are we asking the right questions?

It’s not just in Nigeria or Africa: worldwide, there is no universally fixed “recommended” proportion of a country’s budget for recurrent vs capital expenditure. But, if we start to think for ourselves, we will recognize how uniquely important it can be, for countries at earlier stages of development to free up their budgets from vicious salary cycles. Start budgeting better so we can spend on productivity, capital, systems and institutions, and not just on perennial cycles of consumption and debt repayment.

Whatever questions need to be asked, whatever productivity-focused policy changes need to be acted upon, let us not hold back from these original ideas, basic questions and formative choices.

Where do we start?

A developing country with large masses of poor and excluded people CAN NOT depend on a private led health system. In the sticky web of globalization, public sector leadership can be a literal matter of life and death.

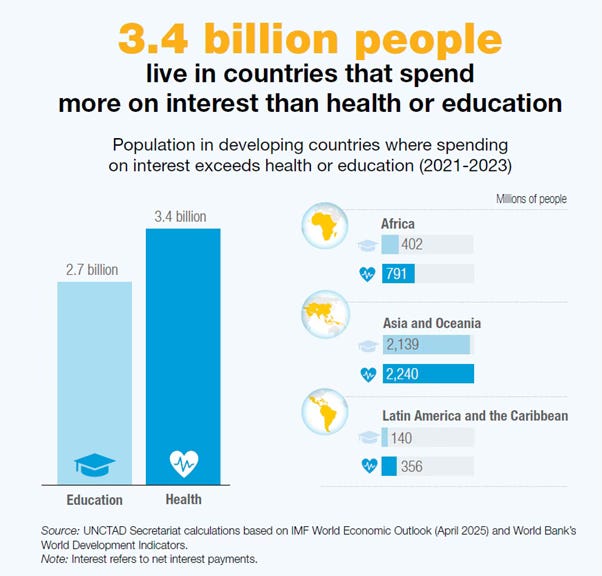

Because most of health supply in Nigeria is private, our Out of Pocket (OPP) payments are among the highest in the world. Donor financing cannot fill the gap. One reason why, is that, for every $1 in aid a developing country receives, over $25 is spent on debt repayment. Donor dependency creates a vicious cycle that actually crowds out public spending on health.

How can we transition away from foreign aid?

In the closing chapters of Global Health in Practice (2022), Dr. Olusoji Adeyi makes stepwise recommendations for pivoting away from foreign aid for health.

We can immediately accept full financial responsibility for the building blocks of health. With better planning, we can budget for essential medicines and basic health services. We can refocus foreign aid toward more complex strategic reforms. This can give us enough time to transition.

The refocused technical assistance can scale up home-grown research networks, think tanks, insurance systems, disease surveillance, manufacturing technology, and integrated health systems. By 2030, our health sector should be locally financed, in line with global consensus on sustainable development.